Paris, 19 September 2016 — La Quadrature du Net publishes an OpEd by Félix Tréguer, co-founder and member of the Strategic Orientation Council of La Quadrature du Net.

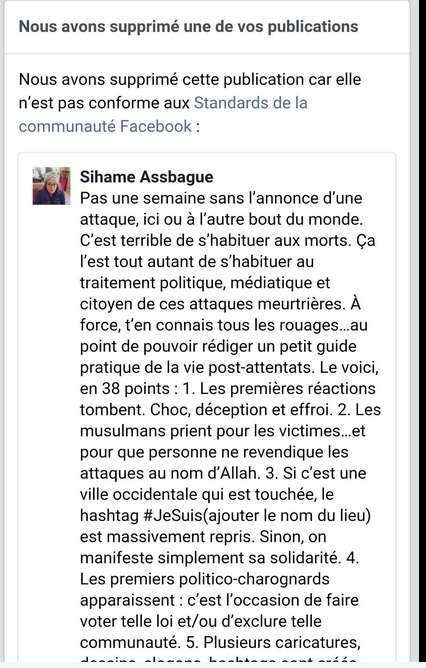

Sihame Assbague is one of the leading representatives of the French “political antiracists”, a new generation of activists that is bringing some fresh air to the struggles against discriminations, police violence and sexism. In late June, Facebook notified her that one of her post, entitled “post-terrorist attack guide”, had been taken down for violating its terms of use.

Probably warned by Facebook users hostile to Sihame’s speech, some subcontractors of the Californian company in charge of enforcing its censorship policy decided to suspend her account for 24 hours. They gave no explanation as to which “community standards” Sihame allegedly breached.

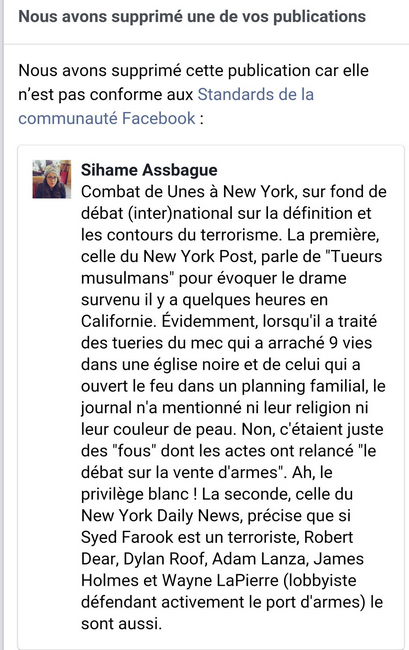

On 11 July, a similar sequence occurred, this time for a critical analysis of the media coverage of mass murders in the United States:

Besides the takedown of the post, Facebook’s punishment was an account suspension of 72 hours.

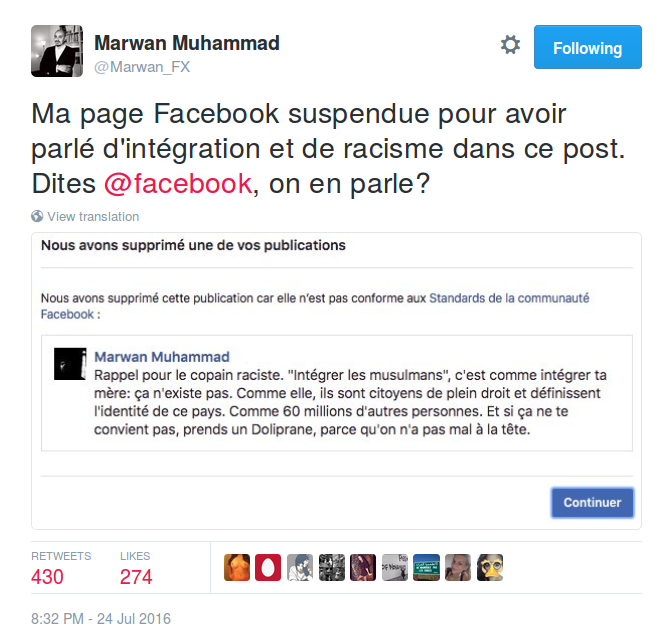

But the summer would bring other surprises. Late July, it was the turn of Marwan Muhammad, statistician and activist of the Collective Against Islamophobia in France (CCIF), to suffer from Facebook’s censorship policy.

Then, in late August, Philippe Marlière, professor of political sciences in London, had his account suspended during five days for having defended the right for women to dress as they wish, during the ludicrous controversy around the “burkini”. Afterwards, Marlière reported that he had spoken with a Facebook employee located in the United States who told him that his account had been desactivated because “numerous people had made a request to that end”.

How did we end up here?

In the past, we have seen such private censorship being practiced in the name of public decency – with the prohibition of works of art by famous painters (the “Origin of the World” by Gustave Courbet), depiction of nipples, female hairiness –, or even of “robocopyrights” deployed in the name of copyright. But so far, for the antiracist movement, Internet platforms have remained spaces where speech was relatively free. Not anymore.

And yet, solutions exist. In 2013, a civil society working group suggested to include in the French criminal code a general provision to punish infringements on someone else’s freedom of expression – a proposal echoing that made as early as 1999 by Laurent Chemla. Among other things, such a provision aimed at preventing online platforms like Facebook – who enjoy special legal protections because of their status of “technical intermediaries” – to use their terms of service to undermine the freedom of expression of their users. The goal was to ensure that these private actors would not turn themselves into judges by imposing contractual rules restricting freedom of expression below what is afforded by the 1881 French law on freedom of the press.1La Quadrature du Net supports the adoption of such rules for technical intermediaries (that do not have any editorial control), providing a means of public expression, and that can be described as “universal” in the sense that they are not addressed to a restricted “community of interest”, the later being defined by the French Court of Cassation as a group of individuals linked by a common affiliation, aspirations and shared objectives.

Coupled with the systematic collection by the police of user complaints against litigious content, with the reinforcement of the means allocated to police and the judiciary and with a notice-and-notice procedure allowing for amicable takedowns, such a procedure would help reconcile freedom of expression with the effective enforcement of its abuse, while respecting the rule of law.2These proposals lead to a device that seems complex but that is balanced: reports of potentially illegal content made on the platforms are systematically transmitted to those responsible for the publication (system called “notice-and-notice”) and also collected by the police. For categories of abuse of freedom of expression considered to be the less serious, a form of amicable settlement would allow the content publisher to take it down quickly if s/he considers that the content in question is actually illegal. For categories of the most serious offenses, preventive action could be initiated by the hosting provider immediately after the content has been reported, or upon request of police to immediately suspend access to this litigious content, pending a court decision that should intervene urgently if the person responsible for the publication believes that his/her statements fall within the freedom of expression and wants to restore access to censored content. The latter will in any case be subject to criminal prosecution if the authorities or possible plaintiff(s) consider it appropriate, a fortiori if s/he opposed the removal of content by refusing the amicable agreement. As is it the case today (even if the provision remains unenforced), abusive reports would also be punished.

But let’s be lucid: In the current context, there isn’t much hope for such a proposal. With every speech and law they make on the issue, politicians make it clear that, for them, the basic safeguards laid down in the 1881 press law – and in particular the judicial protection of freedom of expression – are way too generous to apply on the Internet. Instead, their favored policy option is the creation of public-private censorship assemblages to circumvent the judicial authority.

The disastrous record of the French government

In 2004, during the French transposition of the so-called eCommerce Directive with the adoption of the Law for the Confidence in the Digital Economy or LCEN), the Constitutional Council warned that the “characterization of an illicit message can be tricky, even for a lawyer”.3Les Cahiers du Conseil constitutionnel, cahier n° 17, Comment of the decision nb 2004-496 DC of 10 june 2004. But in the recent years, the government has continued to delegate censorship to large Internet firms, with the support of some non-governmental organizations fighting against discrimination. Homophobia, sexism, handiphobia, apology of violence, prostitution or terrorism have thus been added to crimes against humanity, child pornography and Holocaust denial in the long list of offenses whose punishment is privatised.4While case law abuses had led to the situation against which the Constitutional Council just tried to warn the legislator at the time, the current majority has reinforced these abuses by legislative additions extending Article 6 of the LCEN to new offenses.

At the same time, a law on terrorism adopted in November 2014 transferred the “apology of terrorism” offense from the 1881 press law to the criminal code, in order to circumvent the procedural safeguards that this “great law” of the Third Republic offers to those who express themselves – a move that explains the immediate trials and prison sentences pronounced after the Paris attacks in January 2015 for statements of dubious dangerousness, and which led a body of the UN Human Rights Council to voice its concerns to the French government. The government also extended the administrative blocking of websites originally created for child pornography to “terrorist content”, a dangerous measure that is already proving useless.

Then, in 2015, the political response to the Paris attacks led to three major changes for civil liberties on the Internet. First, the adoption of the Intelligence Act, which validated and normalized programs of mass surveillance and allowed the government to try to evacuate most of post-Snowden controversies (the law was extended this summer again after the attack of Nice). Second, the adoption of the state of emergency, and the hundreds of very controversial computer searches that it made possible. And finally, the extension of extra-judicial censorship for terrorist propaganda. Last year Bernard Cazeneuve, the Minister of the Interior, proudly announced the creation of a partnership in this field between his Ministry and major Silicon Valley companies and telecom firms. Meanwhile at the European level, Europol has developed without any real democratic control a strong relationship with the digital oligopoly, while a pending European directive on the fight against terrorism aims not only to encourage the administrative blocking of websites but also to give a blank check to these developments by calling for enhanced cooperation between private firms and police services.

Private censorship is now of such great magnitude that Internet platforms in turn outsource these tasks to companies in Morocco or India whose ultra-precarious “moderators” are completely unaware of the cultural and legal subtleties of the regions they regulate. These “assembly line” censors often rely on algorithms tasked with identifying terrorist propaganda, and which are bound to play an increasing role in the automated takedown of online content.

Gradually, the judicial protection of freedom of expression is undermined in favor of an alliance between overloaded police services, foreign subcontractors and automatic filters. Without knowing exactly why or how, Sihame Assbague and many others are bearing the costs of these dangerous trends, even though their speech is not only a most useful form of public expression, but also entirely lawful.

Anti-racism in the era of counter-terrorism

Such censorship is all the more concerning that antiracists are often stigmatized in the dominant public sphere. Laurent Joffrin, publishing director of the newspaper em>Libération, recently denied recently the right to assemble on the basis of a shared identity. In the government, Prime Minister Manuel Valls as well as Ministers Bernard Cazeneuve and Najat Vallaud-Belkacem have criticized them for “conforting racialized and racist vision of society”, or accused them of being “partisan of all communautarisms”. As if the denunciation of racism in France – also relayed by organizations as subversive as the United Nations, the Council of Europe or Amnesty International – made these activists the objective allies of both terrorism and structural inequalities.

On “social networks”, these same activists are often subjects to threats or other forms of intimidations. Such was once again the case after the Nice attack, as some Twitter users claimed that Sihame Assbague had “the blood of […] French people on her hands”. Just like those in the United States who have accused the movement Black Lives Matter of being responsible for the shooting of police officers in Texas and Louisiana, some in France do not hesitate to say that antiracist activists play into the hands of terrorists by “radicalising” part of French youths, simply because they call on them to reclaim their rights.

Even an older antiracist NGO such as the LICRA – one of the most active in asking for the extension of private censorship online – did not shy away from comparing these activists to the Ku Klux Klan for organizing a workshop reserved to victims of racism.

At a time where racist speech is being banalised in the dominant discourse, the various forms of censorship that these activists are subject to obviously confirm, if not demonstrate, the reality of the inequalities they denounce. Thus, as emphasised recently by human rights activist Yasser Louati (here), or political scientist Jean-François Bayart (there), the problem actually comes from politicians and editocrats engaging in a securitarian escalation that plays into the hands of terrorists.

Comforted by the intellectual resignation of the political or media elites and by the rise of the self-fulfilling prophecy of a “clash of civilisations” (the latter being a direct consequence of the former), security laws have been piling up in the past years. The harmful consequences of these ineffective laws are being most hardly felt by marginalised groups identified as being from Muslim culture or immigrant origins, who are already victims of structural discrimination. Of course, the racism and inequalities suffered by these groups are not, in and of themselves, a reason to push them towards violent action. However, they tend to reinforce the ability of terrorist propaganda to act as a coherent narrative by presenting Western societies – and France especially – as inherently incapable of offering them a place as rightful citizens and prospects for a better future.

Meanwhile, the neofascists of the far-right are also preparing for the worst. The heads of intelligence services are preaching in the desert to warn against the threat – said to be “unavoidable” – of seeing these hateful groups brutalise part of our fellow citizens, and point out the inadequate means allocated to their monitoring. Meanwhile, hatred is becoming mainstream in political discourse, with the complicity of many editorial boards.

Free speech against hate speech

In this context, antiracist speech is of crucial importance. Even if one can disagree with some analysis or proposed modes of action, the fact remains that these activists help deconstruct simplistic reasonings about the “clash of civilizations”, of which neoconservatives and terrorists alike have been taking advantage since 2001. They rightly remind us that the culturalist, islamophobic or narrow security-driven interpretative frameworks that are building up after each wave of violence actually validate the paranoiac delusions of hate-mongers. They contribute to making visible the daily experiences of those caught between the Djihadist hammer and the xenophobic anvil.

The posts of Sihame Assbague, Marwan Muhammad and Philippe Marlière censored by Facebook aimed to denounce the latent racism in the political and media response to recent terrorist attacks. Everyone has the right to criticize these analysis, but in a polity abiding by democratic standards, we should not doubt their legitimacy, much less censor them.

Of course, there are other avenues for public expression besides Facebook on the Internet.5By the way, activists, journalists or citizens would do better to avoid giving the exclusivity of their public expression to big platforms like Facebook. They should instead only share content published elsewhere on the Web or use free and decentralised alternatives. But network effects are strong. They contribute to the domination of these big platforms and give them control over whole segments of the public sphere. Such a monopoly can only be tolerable if it comes with minimal safeguards protecting freedom of expression.

These episodes of private censorship might also seem to be isolated cases, an epiphenomenon that should not raise alarm. But even if we do not have any transparent information regarding the content takedowns decided by Internet firms, other symptomatic cases have surfaced in the past months and years. In France, journalist David Thomson, a specialist of Djihadism at Radio France International, has been subject to censorship and punishments of all kinds on Facebook (account suspension, desactivation of private messages for several days, etc.) because of posts directly related to his journalist activity. More recently, Facebook has come under worldwide criticism for censoring a canonic photograph denouncing the brutality of the US War in Vietnam.

In light of ongoing policies, such censorship is likely to proliferate in the future. However, neither antiterrorism nor the fight against discriminations should justify undermining the rule of law. Freedom of expression is just as precious to democracy as it is fragile. Now that censorship is affecting those whose contribution to the public debate is so urgently needed, we get a better sense of the antidemocratic effects caused by the state of emergency spreading through the Internet.

References